This time is different?

Polls always move, but this parliament has seen an unprecedented shift in the mood of the electorate

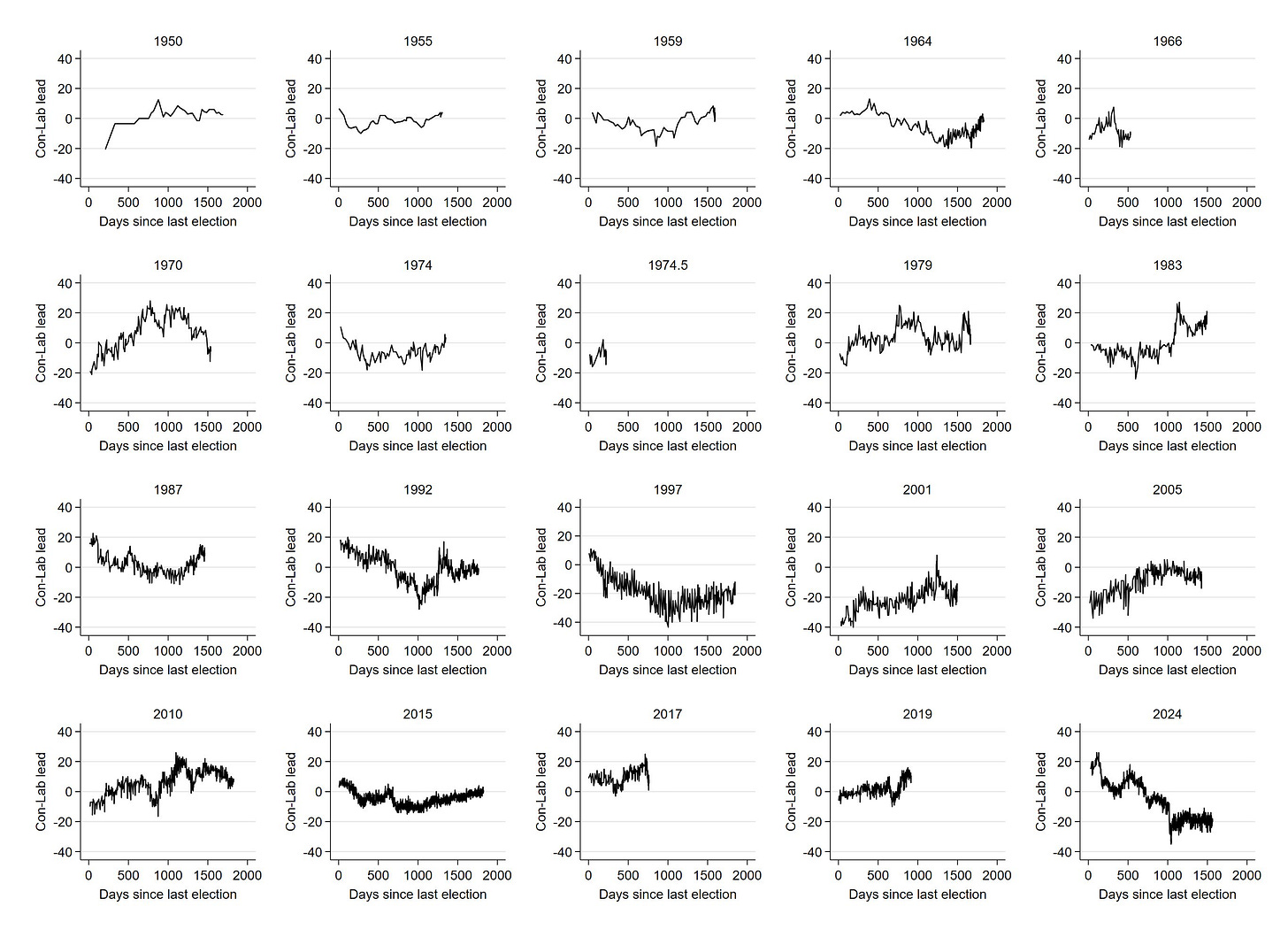

It is easy to offer hyperbolic commentary on politics - crises come and go, voters eventually turn on incumbents - but is there any precedent for the shift in the electoral mood we have seen since December 2019? Drawing on nearly 8,000 historical voting intention polls from over 50 polling firms (see this article for the wider ‘comparative timeline of elections’ project with Chris Wlezien that it is drawn from), it is possible to compare the movement in the polls across every election cycle since 1945.

Let’s start by plotting the Conservative Party’s lead over Labour in voting intention polls. For the purpose of this analysis we don’t smooth or average the data (unless there is more than one poll on the same day). This helps illustrate some of the volatility in the polling numbers reported by different pollsters - an important feature of the data that is often ignored.

In terms of the range of Conservative-Labour poll leads, there has been no parliament where the electoral mood has swung so sharply and viciously. We have gone from the heights of a +26 point Conservative lead during the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ in the early period of the Covid-19 pandemic to a +35 point Labour lead at the height of the Truss implosion: a remarkable 30.5 point swing, higher than observed at any previous election.

It is not the only election to have experienced a seismic shift in the electoral mood, however. Between 1992 and 1997, the Major government saw its lead fall from +11 to a Labour lead of +44 points (a number that should be treated with some caution given the final polls in May 1997 overstated Labour’s eventual vote by around 4.5 points): a swing of 27.5 points.

During the first term of the Thatcher government the Conservatives were briefly 24 points behind but at one point were 27 points ahead after establishment of the SDP and its siphoning off Labour support. Even an election cycle like 1997 to 2001 saw some variation - from an initial honeymoon where Labour was 40 points ahead to a brief period where the party were behind the Conservatives during the 2000 fuel protests.

All election cycles see some ebb and flow of the electoral mood, while some have periods of relative stability. In this electoral cycle so far, the phases that arguably have determined the current state of public opinion are the decline in the Conservative lead following a peak around ‘Freedom Day’ in summer 2021, a sharp drop linked to revelations of the Partygate scandal in November/December 2021 and a further collapse in October 2022 due to the disastrous Truss premiership and mini-budget. As it stands, the Conservative Party’s electoral misfortunes owe to many authors.

The polling since November 2022 is striking for the stability of the Labour lead at around approximately 20 points. Beneath this headline number, however, the Conservative vote has declined (as has Labour’s support), facing a growing threat from Reform.

Can any hope be found for the government from the historical record? There is some evidence that both Conservative and Labour incumbents have experienced ‘swing-back’ - an improvement in their polling position - in the months leading up to an election. These can be seen recently in 2010, 2015 (where the polls under-estimated Conservative support) and 2019. The sharp opposite trend in the weeks prior to the 2017 election provides a reminder that parties can pull off remarkable recoveries.

It is illuminating to alternatively plot the poll lead of the governing party (over the opposition) across these elections. The trend of falling support in the early part of the election cycle and rising support as the election nears can be seen in most cases (even ahead of defeats), but it remains starkly elusive in 2024.

Nothing should be assumed about the future path of public opinion. In May 2021 many (including myself) were ready to write-off Labour’s electoral hopes for a decade following its defeat in the Hartlepool by-election. Now the party stands revitalised. As the polls continue to show a large deficit for the Conservative Party that is stubbornly resistant to events, relaunches and policy offers, it does however seem that time is fast running out for the Prime Minister to turn things around.

The "voting intention" models used by pollsters are nothing but the most amateurish possible forecasts.

They try to build a forecast from a single poll (red flag number one) and that forecast does nothing more than allocate "don't knows" proportionally to decideds.

This is a pseudoscientific approach that discounts the evidence that undecideds lean conservative - and conveniently ignores this is precisely what *just* happened in the Mayoral Elections, and why their "voter intention" forecasts failed miserably just a few weeks ago.

It's a little sad they demand to be taken seriously with a track record this poor