Things could get worse...

Political folklore dictates that there will be swingback to the government before the next election, but might things only get worse from here?

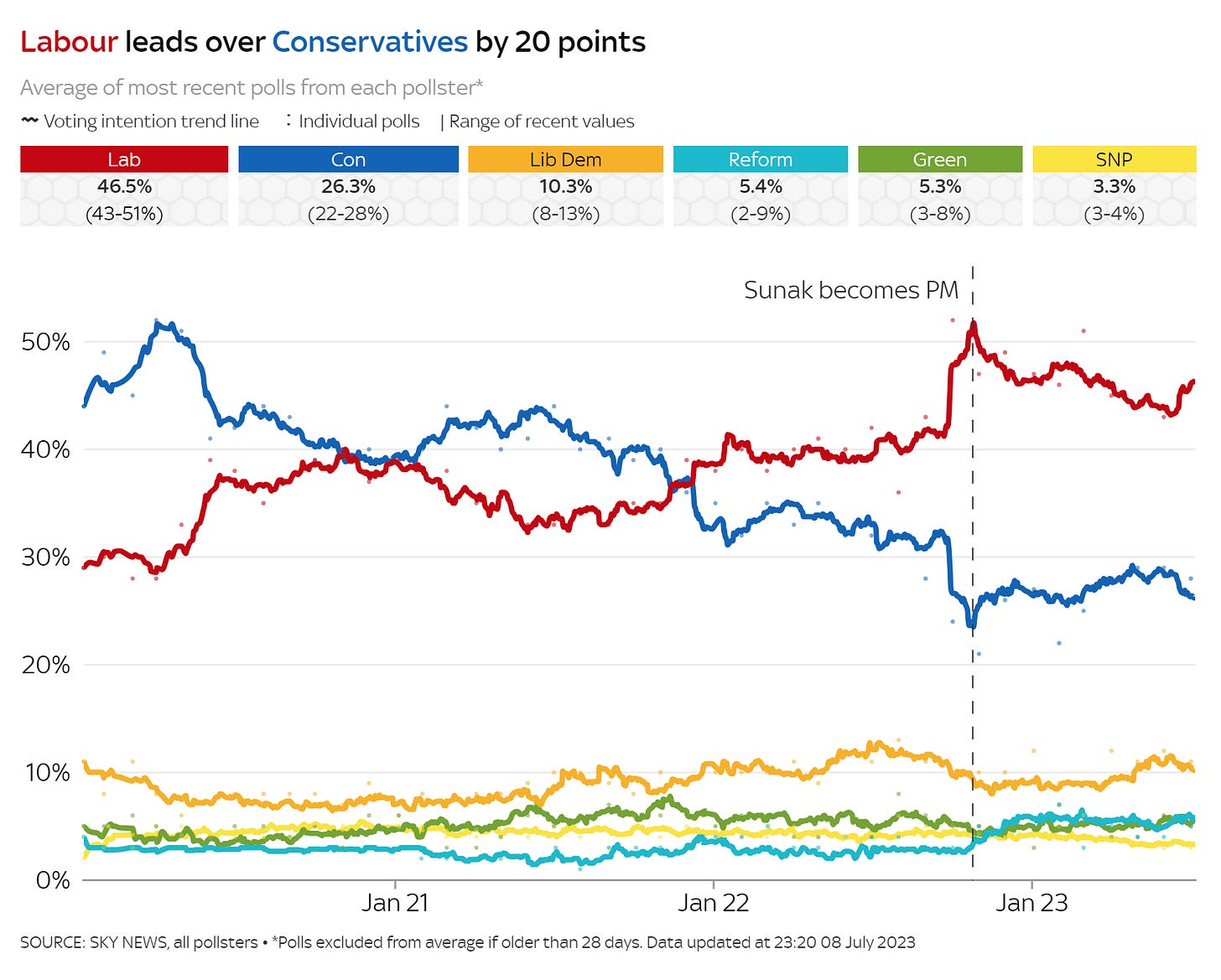

Last month we launched the Sky News poll Sky News poll tracker. Bookmark it, we will be updating it daily.

There was a widespread view after the Truss interregnum that a return to (relative) political normality would see the government - under the leadership of Rishi Sunak - claw back support ahead of the general election. After all, the historical pattern is for governments often to recover from ‘mid-term blues’. Back in February I argued that asking whether the polls would narrow was the wrong question - it was much more important to think in terms of the outlook of ‘the fundamentals’.

To judge whether an upturn in Conservative polling ahead of the next election is likely, therefore, it is essential not to simply assume this will happen because ‘polls have always narrowed in the past’, but evaluate whether the party is likely to preside over significant improvements in ‘the fundamentals’ in the months ahead. Will the economic situation improve for most voters? Will Brexit continue to be seen as a failure? Will the government’s handling of the NHS, industrial unrest and immigration be viewed favourably by the electorate?

The polls can give us important insight into the prevailing political weather, but long-term forecasts should consider the actual experiences of voters vis-a-vis their jobs, the cost of living, their experience of public services, and so on. This sort of argument is consistent with what political scientists call ‘retrospective voting’: that in the ballot box, voters make an assessment on the performance of the incumbent. The additional idea of the ‘costs of governing’ suggests that the accumulation of bad news and negative experiences leads voters to eject incumbents who they think have over-stayed their welcome.

We have seen in polling by YouGov and Ipsos that voters are unconvinced (to say the least) by the government’s performance on its key pledges so far. Perhaps if it can turn around the numbers on some of these, then its polling might improve - but this is not a trivial challenge. Many of the pledges involve deeply structural factors which make it difficult to see how these can be delivered on decisively.

But could things get even worse for the government? There are a number of reasons why it is quite possible, likely even, that the Conservatives will see their polling fall further before it gets better. This could reverse the incremental gains made under Sunak this year, in the aftermath of the Truss premiership.

Firstly, and most obviously, the squeeze of the cost of living is still being felt across the electorate. Polling by Ipsos shows that voters remain economically pessimistic, though not yet quite at the same depths of doom as summer 2022. Some people are being particularly badly hit, but everyone is experiencing some degree of economic distress. The fifteen years of wage stagnation we have lived through has no precedent for contemporary democratic politics. Maybe voters’ short memories will save the government if things start to look better next year (this is not to be discounted as a possibility), but it would be brave to bet on it. Rising interest rates have led to talk of a ‘mortgage timebomb’, and while its impact may be delayed as those will only come into effect gradually, it appears that it will hit hardest voters in Blue heartlands.

On top of this, the government is pushing for wage restraint, in particular in the public sector. This is likely to fuel industrial action in the months ahead. More widely, attempts to dampen inflationary pressures could lead to an economic downturn (as the Chancellor hinted at last month). There will potentially also be knock-on effects of industrial action on public services - it will be more difficult to recruit staff, while waiting lists and other improvements in performance may be more difficult to deliver on the back of a disillusioned workforce. As such, the government has a heroic task on its hand to show it has turned the ship around.

For a long time Rishi Sunak’s popularity outstripped that of his own party. It is easy to forget that as Chancellor he originally won his public popularity through introducing the furlough scheme during Covid-19 - an intervention that was widely liked by voters (it was often mentioned in focus groups that we ran at the time as something that led people to trust government). Now, as PM he is asking many voters to endure a little economic discomfort for the greater good of bringing inflation under control. This offers a rather different public image of Sunak, and his gradually sinking approval ratings highlight that he may not always out-poll the Conservative Party with the wider electorate - especially if he has to be the front man for tough economic times.

Sunak now regularly trails Keir Starmer in poll questions about who would be ‘best PM’. All of this means that the government may not be able rely on Sunak’s greater appeal to the public to win over voters. Keep in mind that just ahead of the general election in 1992, at which the Conservatives won a shock victory, John Major had a net approval rating of +4, while his government had a -36 rating. Sunak’s approval rating varies slightly depending on which pollster one refers to, but the latest polling by Opinium puts him on -26 net approval (Deltapoll -23 and Ipsos -31 find similar ratings, whereas Redfield & Wilton put it slightly higher at -16). Given the tendency for leader’s ratings to decline over time - thanks to those aforementioned ‘costs of governing’ - Sunak’s declining ratings could be an increasing cause for concern for the PM and his party.

All this is before one speculates over how lasting the effects of partygate will be for voters. Sunak potentially missed an opportunity to draw a line under the issue by missing the parliamentary vote over whether Boris Johnson lied to MPs, though had he turned up it could have fuelled tensions within the parliamentary party among those loyal to the former PM.

Looking ahead, the fundamentals for the next twelve months are not especially encouraging. For the government to turn its electoral fortunes around it must hope for an improvement in the economic outlook and turnaround in the wider public mood. The case of the 1983 general election might offer the Conservative Party a sliver of hope that it still has time to turn things around. In 1980-81, the Thatcher government’s adoption of monetarist macroeconomic policies (including high interest rates) to bring inflation under control led to rising unemployment and a period of economic recession. By late 1981 the party was polling in the mid-20s. By the summer of 1983, Thatcher had won re-election in a landslide aided by an increasingly rosy economic outlook.

But Thatcher’s government had been in office just four years, was facing a divided and ideologically exhausted Labour Party led by an upopular leader, and had recently won a decisive military victory in the Falklands War. Perhaps Rishi Sunak will not be quite so lucky with events and his opponents, but it is worth remembering that the future is full of surprises.

Like many of you, I am pondering what platforms to use as Twitter is becoming a less reliable and enjoyable space. You can currently find me on Bluesky, Threads, and Mastodon where I post intermittently.

Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/drjennings.bsky.social

Threads: https://www.threads.net/@prof.jennings

Mastodon: https://mastodon.social/@drjennings

I don't think an SDP will take 25% of the vote to gift a "landslide" of 43% this time! Not sure 1983 is much of a good example. Currently the divided vote between Labour and the LDs seems to efficiently reduce Tory chances

Excellent read Will, thanks.