'Will the polls narrow?' is the wrong question

To assess the likelihood of a Conservative recovery in the polls, it is first necessary to understand why the party's support has ebbed away since 2021.

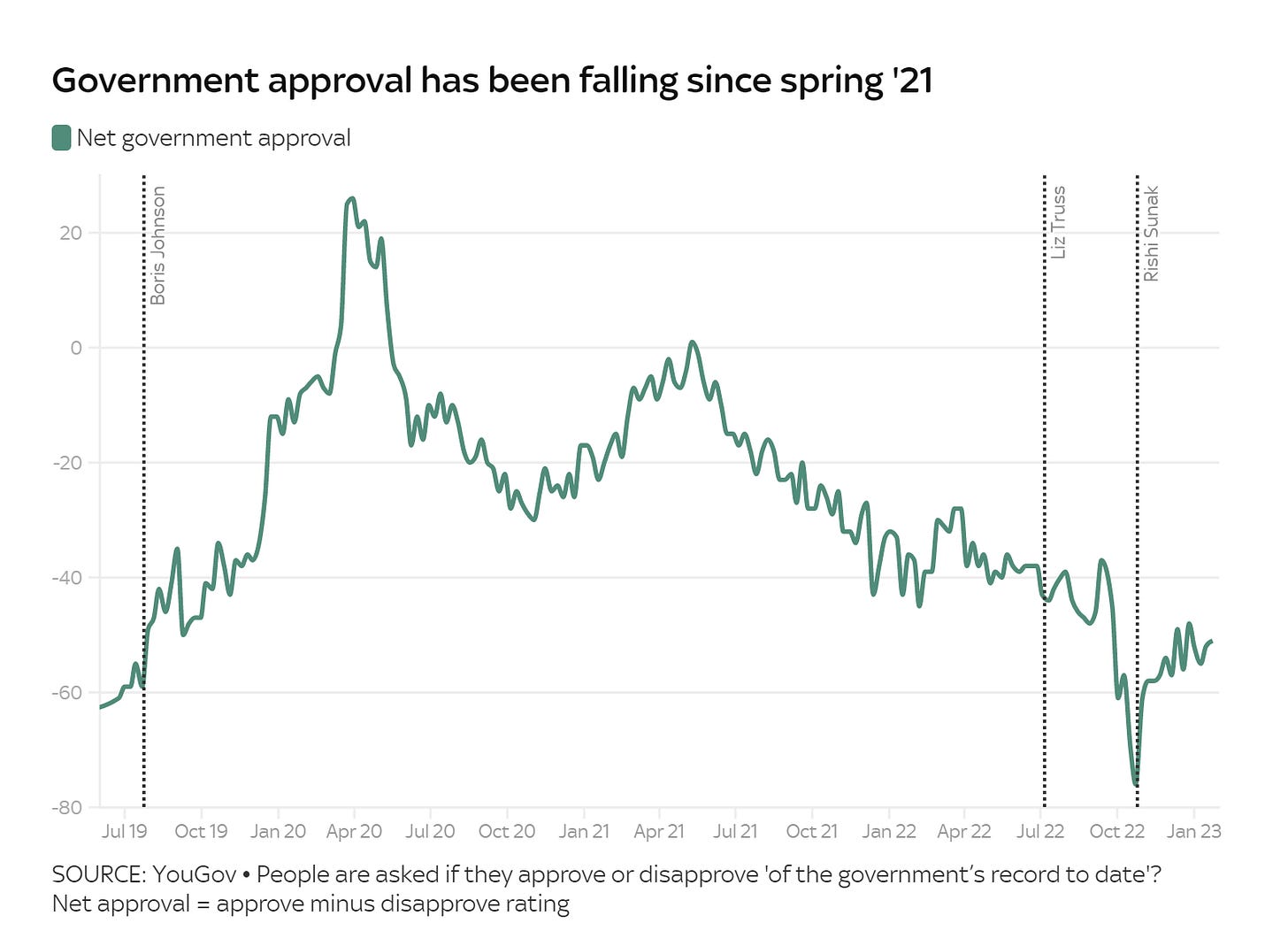

It has become fashionable among pundits to ask whether Rishi Sunak can lead the Conservatives to a ‘1992 style’ escape. Many are assuming the polls will narrow (to some degree) without even asking why the Conservative Party has lost so much support. Indeed, it reflects the growing disconnect between Westminster and the rest of the country that a gradual shift has occurred in public opinion over an extended period of time, yet this has barely registered in political commentary at all. Most seem quite oblivious to the fact that Conservative support had been falling in the polls for well over a year before the Truss-Kwarteng mini-budget spooked the financial markets. As late as October 2021, Tim Shipman was declaring “Boris Johnson now squats like a giant toad across British politics” despite approval of the government having been in decline since spring of that year.

Indeed, there has been little serious reflection on the political and economic ‘fundamentals’ that have driven the popularity of the Conservative Party in power since 2019.

For one thing, the exceptional nature of the Johnson' government’s initial honeymoon - first the supposed closure offered to the nation by ‘Brexit Day’ on 31st January 2020, the ‘rally-round-the-flag’ in response to the initial Covid lockdown, and Britain’s highly successful vaccination programme - has been widely taken for granted, yet it was always likely that these would eventually fade in voters’ minds as other issues emerged on the political agenda. It is arguable that, alongside the luck of fighting the 2019 election against the deeply unpopular Jeremy Corbyn, these circumstances created something of a bubble in support for the Conservative government - a bubble that has since deflated, both gradually and suddenly, as political events and economic conditions have played out.

In turn, those who would Bring Back Boris are strangely silent on the party’s shrinking popularity under the former PM between April 2021 and July 2022, when Conservative MPs finally forced him to stand down. ‘Partygate’ revelations before Christmas 2021 led to a drop of around 5 points in support for the government. While this had started to creep up again by spring 2022 the overall trend from summer 2021 was distinctively downhill.

Similarly, the Truss government’s infamous ‘mini-budget’ appears to have inflicted well over 5 points of damage to Conservative polling. And while Rishi Sunak has been able to staunch the haemorraging of support, the trend remains stubbornly downward in the longer-term.

While different factions in the Conservative parliamentary party have been quick to point the finger for the party’s polling troubles variously at Johnson, Truss or Sunak, the more complicated reality is that there is no one individual to blame and that more structural forces appear to be at work. This is especially apparent if one focuses on voting intentions for the Conservatives only, where events such as the Partygate revelations and the mini-budget seem to more accelerate trends than truly go against the tide of public opinion.

If one inspects the polling data closely it becomes evident that the spring of 2021 marked a turning point in approval of the Conservative government. This was the period in which the threat of Covid was perceived by many to have receded. It could be argued that events since have in part reflected an unwinding of the Covid ‘rally’ in government support and accumulation of what political scientists call the ‘costs of governing’ (things such as bad news stories and policy decisions that alienate specific subgroups of voters - gradually weakening the electoral coalition of the governing party).

It is also noticeable that it was around the same time that the percentage of voters believing that Britain was wrong to vote to leave the EU started to tick up inexorably. The signature policy of the Conservative government has thus become increasingly unpopular with voters. This starves it of the wedge issue that it has used, to great effect, against its opponents - especially the Labour Party in 2019 - since the EU referendum in 2016.

A peculiar feature of contemporary British politics is how heavily the significance of economic factors are discounted by many commentators. In part this is an understandable reaction to the ineffectiveness of economic arguments in the 2016 referendum campaign. Yet the bleak economic situation we face as a country - with real wages stagnant over more than a decade - should not be ignored as having potential political consequences. Growing economic confidence from winter 2020 to spring 2021 arguably contributed to rising popularity of the Conservatives in the polls - as the country became more optimistic about the path out of the pandemic. The rising cost of living since autumn 2021 has coincided with a decline of Conservative support.

Using polling data that goes back to the 1950s, it is possible to track the rise and fall of the Conservative and Labour Parties' reputations for economic competence. These trends have typically been shaped by economic shocks for parties in government, while oppositions have often needed to regain voters' trust over an extended period. Notably, 2022 marks the first time that Labour had overtaken the Conservatives since 2007.

Some might be tempted to put this implosion of the Conservative Party’s reputation for economic confidence at the door of Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng. However, by exploring the trend for the same survey items at monthly intervals over the past three years it becomes clear that the Conservatives’ perceived handling of economic issues has been on the slide since early 2020 and that the Truss premiership represented only a small (downward) blip in a sustained trend over time that started under Boris Johnson (when Rishi Sunak was Chancellor). This data also highlights how Labour has steadily and quietly been building a reputation for economic competence at the expense of the government.

To judge whether an upturn in Conservative polling ahead of the next election is likely, therefore, it is essential not to simply assume this will happen because ‘polls have always narrowed in the past’, but evaluate whether the party is likely to preside over significant improvements in ‘the fundamentals’ in the months ahead. Will the economic situation improve for most voters? Will Brexit continue to be seen as a failure? Will the government’s handling of the NHS, industrial unrest and immigration be viewed favourably by the electorate?

I hope they won't. Narrow, I mean. Good to see you here, anyway. You were one of the most thoughtful observers of UK politics over at the bird place, but I don't go there since Lord Kek took over and started wrecking things.