Despite what you may have heard, the British public are increasingly liberal and left-wing

Britain’s electorate today is more liberal on cultural issues and more left on economic issues than it was when we last went to the polls in December 2019.

A recurring theme of a simplistic, populist strand of Westminster commentary is that liberal metropolitan elites running the country are deeply out of step with a public that leans right on social issues. There is no doubt a certain kernel of truth to this (minus the facile populist spin), and arguably ‘twas ever thus - part of the electoral triumph of New Labour was built on appealing to socially conservative values of the party’s traditional working class supporters and also to middle England, on issues such as crime and education. (I could read Blair’s ‘tough on crime’ New Statesman essay from 1994 again and again - it is the quintessential example of how to build an argument that appeals to both liberal-left and socially conservative values, without coming across as cynical triangulation.)

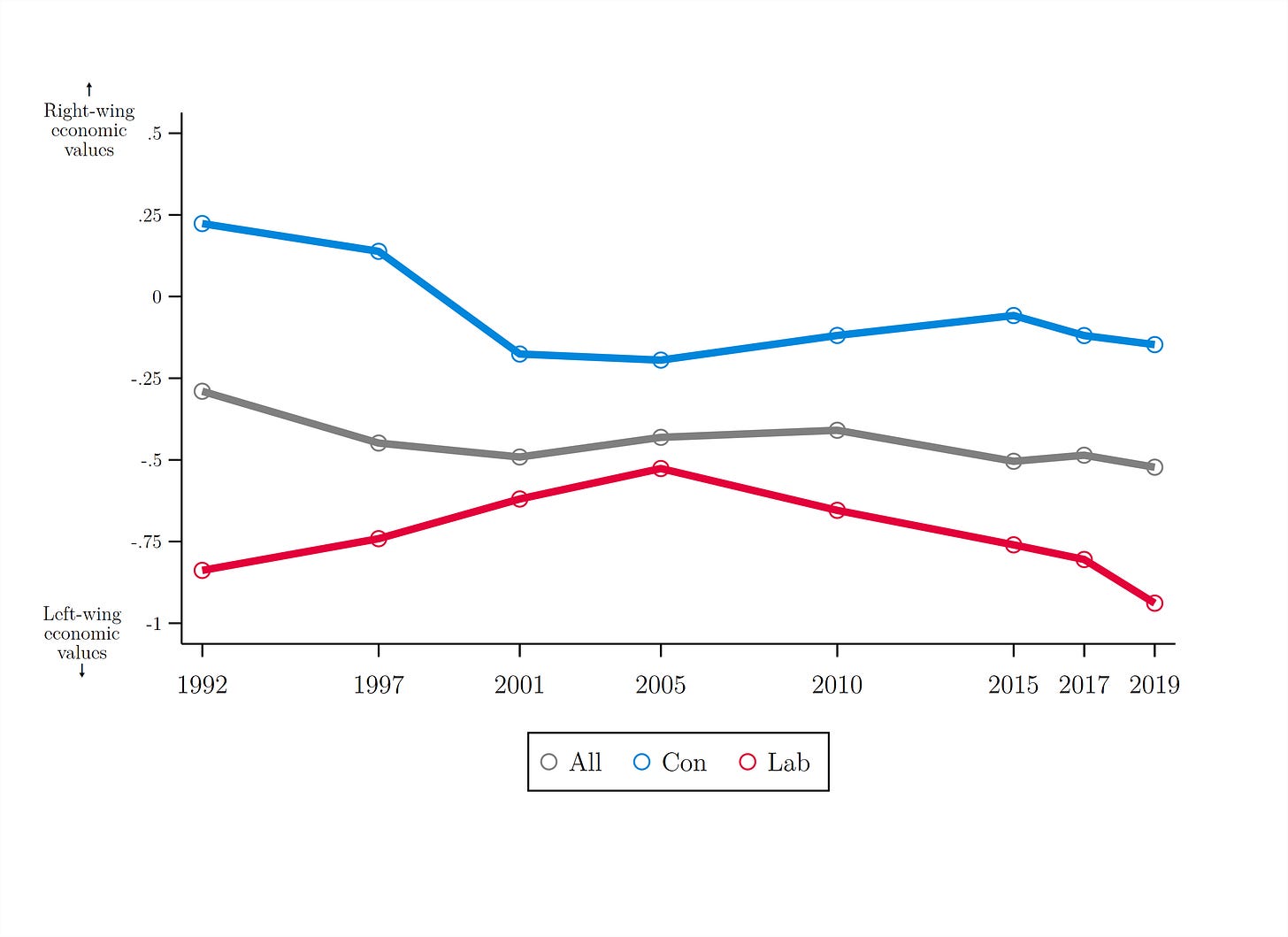

From reading some of these commentators, one could be mistaken for believing that the British public had moved decisively rightwards on both economic and cultural issues. But precisely the reverse is true. Using data from the British Election Study (BES) (thanks to the analysis of Paula Surridge in The British General Election of 2019), it is possible to measure where voters sit on a left-right scale of economic values using a series of survey items asked regularly since 1992. This includes four of the five items from the original Heath et al. (1994) scale to enable comparisons over time.

‘Ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth’; ‘There is one law for the rich and one for the poor’; ‘There is no need for strong trade unions to protect working conditions and wages’; ‘Private enterprise is the best way to solve Britain’s economic problems’.

Below we see plots for all voters, on average, and Conservative and Labour voters at each general election. It is clear from this that the electorate as a whole has moved leftwards on economic issues over the past thirty years, and notably so since 2010, having slightly moved rightwards between 2001 and 2010 (more on that ‘thermostatic’ dynamic of public opinion later).

If we zoom in on the 2015 to 2022 period, using data from the BES Internet Panel (BESIP), voters have move significantly leftwards since the 2019 election and in particular since the summer of 2021. This data has the advantage of large samples for each wave (typically 25,000-30,000 respondents) and the full set of items for the composite scale.1 It is interesting that there was a shift to the right on economic values in the wake of the EU referendum, that has since been reversed. There is a palpable sense in which the British public increasingly believes that government should redistribute from the rich to the poor, that big business is not to be trusted, that ordinary people do not get their fair share, that there is one law for the rich and the poor, and that companies will try to get the better of workers if they get the chance. In this context, it becomes rather less surprising that Labour have gained considerably in the polls since summer 2021 - aided by the rising cost of living and a government often mired in scandal and controversy.

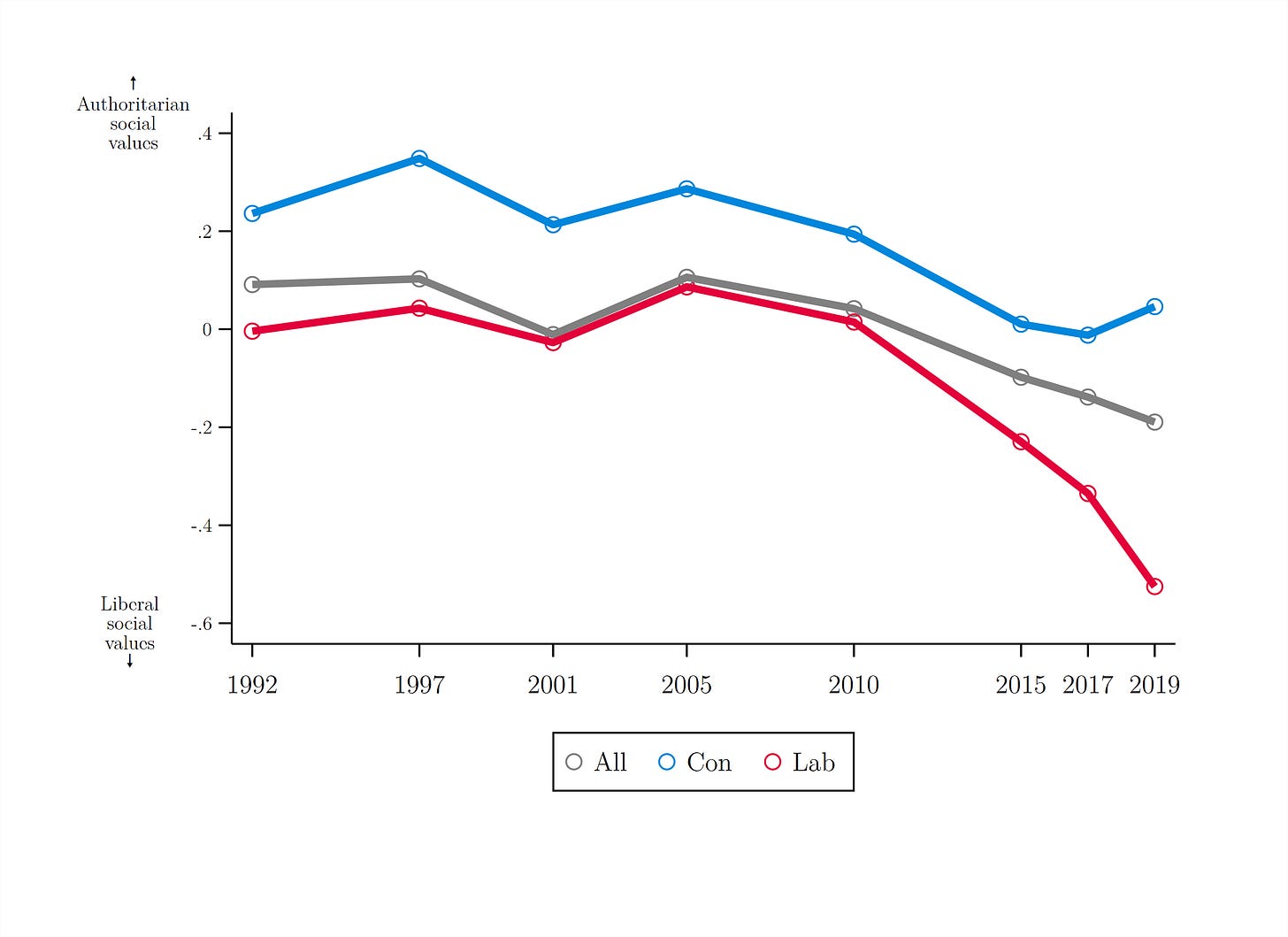

If we turn to the subject of intense debate - the social liberalism of British voters - it becomes clear that the public is increasingly liberal on cultural issues. Here the scale uses the survey items below (but we also know that voters are increasingly liberal on questions relating to gender, sexuality and race, to name but a few).

‘Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values’; ‘Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards’; ‘People in Britain should be more tolerant of those who lead unconventional lives’; ‘People should be allowed to organise public protests against the government’.

This growing social liberalism is a steady trend since 2005 and applies to all voters (though not evenly). In terms of understanding the electoral consequences, the distance between party supporters and the average voter is worth reflecting on. In 2019, Labour voters were more liberal than the average voter by a greater distance that at any point in the last thirty years. The party’s vote has increasingly become more socially liberal than the electorate since 2010 - hence there being some element of truth to the claim Labour’s vote has grown somewhat out of step from the electorate overall. It is a stretch, though, to argue that Labour supporters are all ‘hyper-liberals’, just as it is just not credible to describe the Conservative vote as a whole as ‘radical right’. Indeed, the social conservativism of the Conservative vote in 2019 was further from the average voter than it had been for many elections - both parties polarised to some degree on the cultural dimension (part of this is just mathematical, holding all else constant, if the Labour vote becomes much more socially liberal then the Conservative vote will become relatively more socially conservative than the average voter by construction).

Data from BESIP further confirms that the public has continued to move in a liberal direction since the 2019 election (with this data confirming a pronounced shift in public attitudes since 2015). While key groups of voters, with electorally significant geography (i.e. Leave voters in the so-called ‘Red Wall’), may hold socially conservative values, British society overall is headed in a more liberal direction.

Other measures of left-right and liberal-authoritarian values are available of course. The BES Internet Panel also asks respondents to locate themselves and the political parties on a left-right scale from 1 (left) to 10 (right). Plotting these together on the same (full) scale, as below, slightly obscures the variation over time - but it is still evident that since the 2019 election the Conservatives have been as further right than under David Cameron by voters who themselves have moved somewhat to the left. Interestingly, since 2019 and the departure of Jeremy Corbyn Labour has steadily been seen to be moving towards the centre. This should not surprise, but it provides useful context for understanding why Labour seem to be gathering support at the present moment.

We can marshall further evidence to back up this account of the tide of British public opinion turning leftwards. Data from the British Social Attitudes survey (to 2021) suggests that there continues to be substantial support for increases in taxation and spending - though this measure of support for state interventionism peaked in 2017 (data for 2022 is not yet available - so we may yet have to adjust our understanding of public support for a larger state, as it stands today). Recent polling by YouGov suggests that support for spending vs taxation has fluctuated somewhat over the last 18 months.

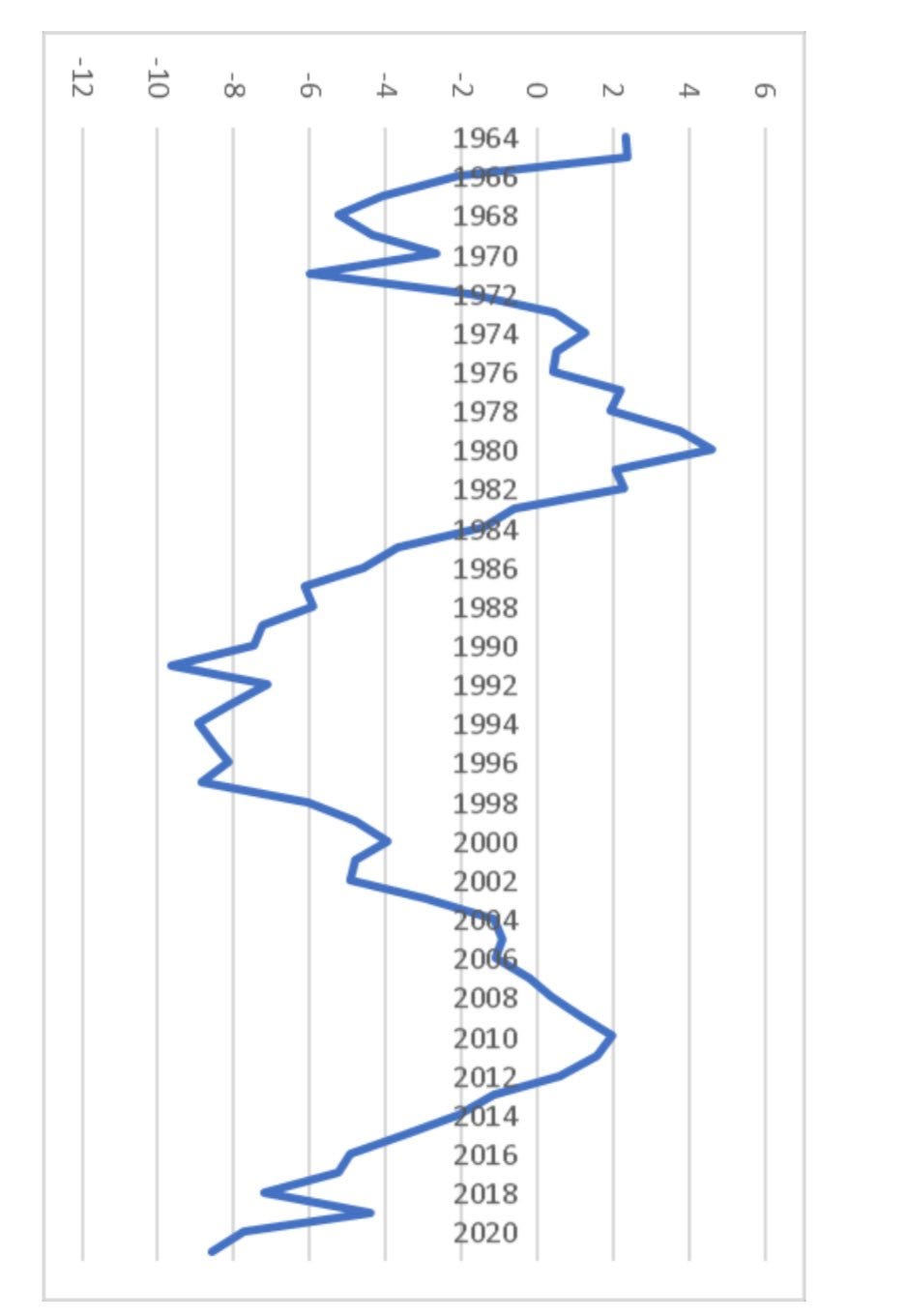

John Bartle’s measure of ‘public policy mood’ (developed based on the theory and method pioneered by James Stimson in the US - which aggregates public preferences across all available survey items and extracts the common variance) suggests that the public is more left on economic issues than at any point since 1997. By this account we could soon reach an inflection point, though note that in the 1990s the measure reached its furthest left point just before the 1992 election, yet it still took Labour another five years to win power.

A key observation from this long-term data series is how public attitudes tend to react against the current government. This is what Christopher Wlezien famously characterised as ‘thermostatic public opinion’ - while the public often have weakly formed specific preferences for policy (given the power of framing effects, reliance on heuristics in low information contexts, instability of survey responses - Zaller 101 for the political scientists out there), they are able to recognise when government is doing ‘too much’ or ‘too little’ on an issue and react accordingly.

The tendency observed in many countries is thus for voters to respond in the opposite ideological direction to the government of the day. In cases where a party has been in power a long time, as now (and also in 1997 and 2010), there is a lot of incumbent policy to react against. If there were a change of government in the near future, those on the left would be advised to recognise that the tide of public opinion may quickly turn - even against a popular and competent administration.

A huge amount of commentary about the ‘realignment’ of Brexit politics, and how Brexit forged a new electoral alliance for the Conservative Party, is silent on these deep underlying shifts in public opinion - an electorate that is increasingly liberal on social issues and leans left on the economy. This is especially apparent in calls to throw policy red meat to the Red Wall in the form of tax cuts and declaration of a ‘war on woke’ (in the form of talking a lot, paradoxically, about what can be said in the teaching of British history and freedom of speech). Attempts to divide the electorate on both economic and cultural lines are complicated by these shifting tides of public opinion. As a final illustration of this, the chart below depicts the trend for social liberalism vs conservativism between 2015 and 2022 for respondents in ‘Red Wall’ and non-Red Wall constituencies (using the original classification developed by James Kanagasooriam). While voters in those constituencies are more socially conservative than voters in other places, they have still been trending in a socially liberal direction over this period! There are liberals in the Red Wall too.

Selective reading of opinion polls designed to capture stereotypes of certain groups of voters may give us a misleading impression of whether the same dynamics that played out at the 2019 election continue to be relevant today. As John Bartle and colleagues observe, the political centre moves, and it would be unwise to assume that voters are not updating their preferences in response to changing circumstances. The growing tax burden and sustained pressure on the cost of living could yet see voters’ views on the economy shift rightwards, while constant hyping of hyper-liberals, woke activism and political correctedness gone mad might yet stimulate a ‘thermostatic’ response from public opinion. What we can be sure about, as it stands, is that Britain’s electorate today is more liberal on cultural issues and more left on economic issues than it was when we last went to the polls in December 2019.

These are composite scales each based on five survey items (using a five-point scale: ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘strongly disagree’ and ‘don’t know’), as listed below:

Left–right: ‘Government should redistribute income from the better off to those who are less well off’; ‘Big business takes advantage of ordinary people’; ‘Ordinary working people do not get their fair share of the nation’s wealth’; ‘There is one law for the rich and one for the poor’; ‘Management will always try to get the better of employees if it gets the chance’.

Authoritarianism-liberal: ‘Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values’; ‘For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence’; ‘Schools should teach children to obey authority’; ‘Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards’; ‘People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences’.

Anthony Heath, Geoff Evans and Jean Martin, ‘The Measurement of Core Beliefs and Values: The Development of Balanced Socialist/Laissez-Faire and Libertarian/Authoritarian Scales’, British Journal of Political Science, 24 (1994): 115–58.

Very interesting data on consistently left shifting trend in the UK attitudes, both economically and socially. That said, while the economy related statements seem to capture the gist well, the "socially liberal/authoritarian" items appear to completely miss two issues on which the majority of the current culture war is fought: immigration/cultural integration and trans(gender) controversies. While one can argue that the latter is of interest largely to the permanently-online disaffected-activist youth and metropolitan chattering classes / academia, the former is more of a universally recognised issue.